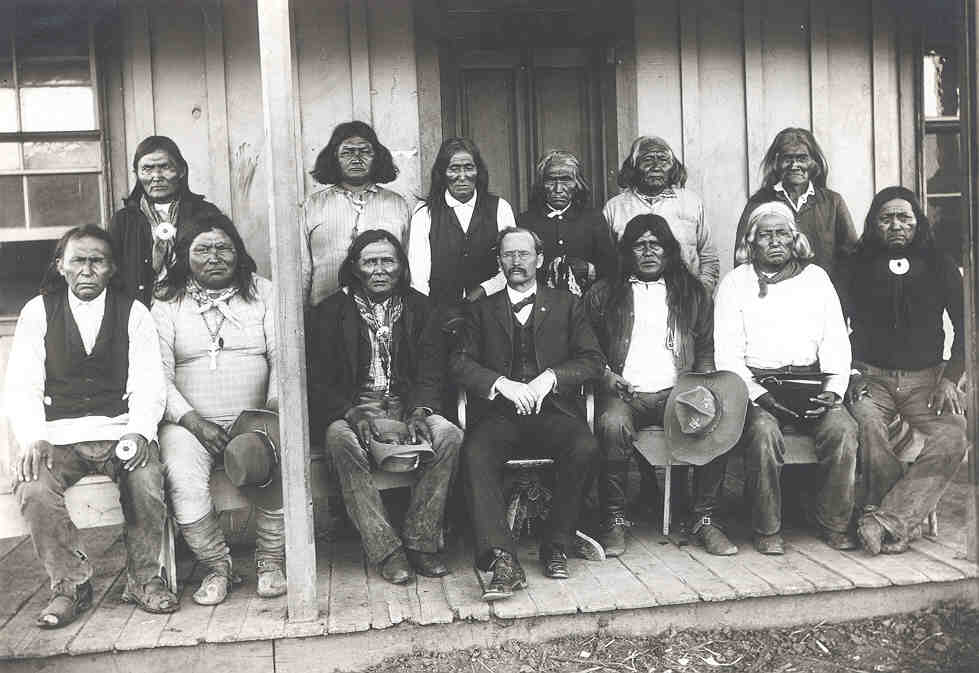

Carl Harberg of Lowenstein and Strauss with Jicarilla Apache Chiefs, 1890, Mora, New Mexico.

Native American Art

The following information is for educational purposes only. It does not constitute legal advice. Every situation is different. Please contact our firm for an appointment to discuss your specific concerns.

Introduction

Laws affecting the trade, possession, and rights of ownership of Native American art affect hundreds of thousands of Americans. There have been important changes to US law in recent decades as a result of passage of the 1979 Archaeological Resources Protection Act and the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. In recent months, concerns have arisen over 2016 proposed legislation, (S. 3127 and H. 5854) that would expand criminal penalties for trading in certain items, enable seizure and forfeiture on cultural objects on export, and require repatriation to tribes, without, unfortunately, providing the clear notice required by due process or a legally and practically tenable system for achieving the legislations’ goals.

The collecting of Native American art is an important contributor to the national economy, particularly in the southwestern states and Alaska. The market in contemporary Native American art is estimated to be between 750 million and a billion dollars. The antique Indian art trade is only a very small percentage of that number. There are hundreds of art galleries and thousands of Native Americans who sell Native American art for their livelihood. The annual Santa Fe Indian Art Market brings over 170,000 tourists to New Mexico a year. The city of Santa Fe estimates that the Indian Market brings in 120 million each year in hotel and restaurant revenue alone. Laws affecting the trade in the small antique segment of the market may have a significant effect on the market as a whole, as casual collectors and tourists may not distinguish between old and new or sacred and profane. The difference is often unclear even to experts. The current public uncertainty about the state of the law is therefore damaging to the Indian art market and the livelihood of Indian artists.

Almost all art collectors seek to stay within the parameters of the law. Unfortunately, the provisions of state and federal law pertaining to Native American art and artifacts can be confusing and even contradictory. Traditional U.S. property rights are based on individual ownership, contract, purchase and title. Many tribes reject these structures as imposed by a dominant, foreign culture, believing that communal ownership trumps individual rights, or that oral tradition should take precedence over systems ordinarily used to determine rights over property. Today’s laws on the possession and transfer of Native American artifacts reflect the tension between these different perspectives.

Alaska Indian Baskets, Frank and Frances Carpenter Collection (Library of Congress), between 1890-1925, cph 3c23596 //hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c2359.

History

Collecting of Indian artifacts has taken place as part of early explorations to map the continent, in 19th century military campaigns and seizures of Native property, by early 20th century historical societies established in thousands of small towns across America, through Christian proselytizing that discouraged Native religions, university and museum expeditions to build study collections, and by individual collectors, large and small. During the late 19th century, commercial pot hunters and expeditions from U.S. and foreign museums brought literally tons of artifacts out of the Southwest alone, and Congress grew concerned over these uncontrolled excavations.

Congress passed the American Antiquities Act in 1906, creating national monuments in Indian Country and requiring permits for excavation. The Antiquities Act helped to stop competition over prime sites but the field remained open to many small archaeological societies and museums. In practice, Native Americans, local ranchers and traders, casual tourists and others continued to collect artifacts for themselves and for the market. Laws against illicit digging were not enforced.

Public and academic interest in both Native philosophies and Native art became widespread in the 1960s and 1970s. At the same time that the Indian art market was expanding, there was a rise in Native American political activism; tribes demanded recognition of Native American religion, and archaeologists urged site protection and scientific study.

When Congress passed the Archeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA) in 1979 and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in 1990, it recognized that both scientific and human interests had been long disregarded. Earlier laws protecting archaeological sites had been barely enforced and Native American tribes had been unjustly denied their right to the remains of their ancestors and to traditional religious and ceremonial objects necessary to tribal identity and well-being. At the same time, Congress emphasized that archaeologists, tribal members, and collectors could each make important contributions to the public’s knowledge and appreciation of Native American cultures.

ARPA, NAGPRA and Federal Laws Prohibiting Theft or Destruction of Government Property

Today, the primary laws that impact collecting historic and prehistoric period Native American art are ARPA and NAGPRA. ARPA prohibits excavation without a permit on federal and Indian lands and trafficking in archaeological resources that have been illegally removed. NAGPRA is focused on the repatriation of human remains and ritual objects to tribes from any museum, institution or State or local government agency that receives federal funds. Other federal laws deal with the theft of objects from sites on government and Indian lands or damage to ruins or graves.

Both ARPA and NAGPRA contain umbrella provisions that vastly increase their scope. Under the federal regulations dealing with archaeological resources, 43 CFR 10, if an archaeological resource was at any point in its history excavated or removed in violation of any federal, state, or local law, then it is illegal to sell, purchase, exchange, transport or receive it after passage of ARPA in 1979 or NAGPRA in 1990.

No matter how long ago an illegal act took place, it is possible that a resale or transfer today can trigger a new violation of ARPA. This could mean, for example, that it would be illegal today to buy or sell an object that was removed 50 years ago from private land in violation of a local trespassing statute. The earlier violation could no longer be prosecuted. However, an ARPA charge could be made based on the date of the resale or transfer of an unlawfully acquired object.

Every case, every sale or transfer is fact-specific. It is important to know as much as possible about earlier transactions, including where an object came from, when it was removed, and whether there was permission to remove it. Because the earliest law applying to artifacts, the Antiquities Act, was passed in 1906, even an artifact that has circulated in the market for a long time can be unlawful to sell, trade, or even donate to a museum if it can be proved that it was removed illegally after 1906. A virtually identical object from private lands is perfectly legal to buy or sell. An object excavated with a permit by a museum and later sold is legal. As a practical matter, there is often greater concern about objects removed post-ARPA, after 1979, and post-NAGPRA, post-1990. Obviously, there are many situations where no one knows where an object was found or how it came on the market. In these circumstances, the burden of proof would be on the government to show that there was a violation of law at some point in the chain of transfers.

ARPA has very broad definitions of “archaeological resource” and “item of archaeological interest.” An item subject to ARPA must be 100 years old but need not ever have been buried. Under the law, it is an object “capable of providing scientific or humanistic understandings of past human behavior.” The type of items considered archaeological resources include pottery, basketry, bottles, weapons, weapon projectiles, tools, structures or portions of structures, pit houses, rock paintings, rock carvings, intaglios, graves, and human skeletal materials. Fossils and paleontological specimens are not archaeological resources unless they are found in an archaeological context. The prohibition against trafficking in archeological resources in ARPA specifically excludes arrowheads found on the surface of the ground.

NAGPRA has two main objectives. First, it protects Native American or Native Hawaiian ownership rights to culturally significant items, human remains and funerary objects found on federal and tribal lands. Second, it requires inventory and repatriation of remains and culturally significant items now in museums and other institutions to tribes that claim them. (Trade in human remains, even from private land, is also generally prohibited by other State and local laws.)

NAGPRA applies to all “culturally significant” materials that are discovered on Federal or tribal lands after November 16, 1990 and makes trafficking in Native American human remains and cultural items from federal and tribal lands a criminal offense.

Artifacts, even of great cultural significance, that are found on private land are legal for individuals to own under NAGPRA, although they may not be immune to other types of claims. However, if the same objects are donated to a museum that receives federal funds, the museum may be required to repatriate the artifacts to a claiming tribe.

Under NAGPRA, “cultural items” include human remains and both “associated” and “unassociated” funerary objects (objects reasonably believed to have been with remains), “sacred objects,” and “cultural patrimony.” “Sacred objects” are ceremonial objects needed by religious leaders for the practice of Native American religion today. “Cultural patrimony” means an object having ongoing historical or cultural importance to a tribe. “Cultural patrimony” can include objects that were legally possessed by individual Native Americans but could not be sold or given away because the community regards the material as owned by the community rather than individual property.

Tribes may assert that they have communal ownership of an item sold by an individual tribal member and that the sale was illegal. As part of a prosecution or defense, tribal elders may be called in to give expert opinion on whether an object is communally owned. The difference may not be obvious, or ultimately, provable. It may be based on theories about how the object was previously used or whether it was blessed.

Other federal laws are used both to protect archaeological sites and to aid claims of tribal ownership. Federal law 18 U.S.C. 1361 protects any U.S. government property from willful or attempted depredation. “Depredation” has been defined as plundering, robbing or pillaging. This law prohibits damage to lands, sites, and resources under the land.

Another federal law, 16 U.S.C. 641, applies to theft or embezzlement of any “thing of value” of the United States or any department of the U.S. The theft provision applies to items taken from either federal or Indian lands. The embezzlement provision was originally focused on organized crime and Indian casino gambling.

In the context of the art trade, it is considered embezzlement when a tribal member sells an object that he had a legal right to possess, but the item actually belonged to the tribal community. There is no minimum age requirement for the object as under ARPA. This law has been used in cases involving ritual masks and medicine bags that a tribal member sold to someone outside of the tribe. It is easy to see that there would be possible confusion with apparently legitimate, lawful activity. There have also been recent government claims that 16 U.S.C. 641 makes it illegal to pick up arrowheads from the surface of federal lands, although ARPA expressly permits it.

Birds and feathers, ivory and endangered species

Laws written long ago to protect bald and golden eagles and migratory bird species from over-hunting can have unintended consequences for collectors and dealers today. Most people are aware that artifacts containing bald or golden eagle feathers may not be sold; far fewer realize that it is a crime to sell, and sometimes even to possess an object decorated with feathers from the most common wild birds. One reason for this split in understanding is that the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act has been strictly enforced, whereas prosecutions for trading in violation of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act are rare. Nonetheless, art dealers and collectors must be aware of the full range of the laws.

The Bald Eagle Protection Act was originally passed in 1940; golden eagles were added to the Act in 1962 because the two birds were often confused by hunters. It is not legal to buy, sell, or barter bald or golden eagle feathers or parts regardless of when the birds were killed or collected. It is illegal even to possess feathers or parts of these eagles that were killed or collected after those dates. Feathers and other parts collected before passage of this law are legal to possess, transport, and give away, but not to sell. A sale may not be disguised as a gift – one cannot sell a feathered object without the feathers and then “give” the feathers to the buyer.

A 1962 amendment allowed Native Americans from federally registered tribes access to eagle feathers through a permitting system that distributes the feathers for ritual use. Eagle feathers acquired under a permit ordinarily may not later be transferred to another person.

The earliest Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) was passed in 1918 to protect declining populations of birds that were hunted for sport, food, and feathers for ladies’ hats. Between 1918 and 1976, four international conventions were signed by the U.S. to protect migratory birds from commercial destruction. With recent additions, over 1000 U.S. bird species are now listed under the MBTA. Originally, prosecutions under the MBTA were focused on baiting and commercial hunting. More recently, the MBTA has been used to allege that sales of antique Native American objects decorated with migratory bird feathers or claws are criminal acts.

Under the MBTA, feathers or bird parts that were legally collected prior to the signing of the treaties in which the species is listed are legal to possess and transport without a permit. They may not be imported, exported, purchased, sold, or bartered. All shipments of bird parts must be specially marked.

Under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), items made of endangered species that are more than 100 years old are legal to buy and sell. Buyers should be wary that if the same species are listed under another law, such as the MBTA, or other federal or state environmental legislation, a sale that is legal under the ESA may be illegal under another law. Some state’s laws expand federal endangered species protections, others cover species protected in that state alone.

The trade in walrus ivory is an important legal issue for Native craftsmen, collectors and dealers. The Marine Mammal Protection Act protects sea otter, walrus, polar bear, dugong, and manatee. The Act prohibits the taking and trading of marine mammals and their products but allows certain exemptions under State management. New marine mammal ivory may be carved only by Alaska Natives and sold only after it has been carved. Old ivory can be carved by non-Natives. Fossilized mammoth ivory may be used by both Alaska Natives and non-Natives. Beach-found ivory is legal to own if registered, but cannot be bartered or sold. Fossil ivory may not be collected on any State or federal lands but may be collected on private lands with permission of the owner.

Finally, the oldest U.S. environmental law, the 1900 Lacey Act, provides umbrella coverage making it a crime to import, export, transport, sell, receive, acquire, or purchase any fish or wildlife or plant if any U.S., state, Indian tribal, or foreign law was violated in its taking, import, export or sale.

Materials from endangered species were, and sometimes still are used by Native craftsmen to decorate American Indian and other forms of tribal art. Many Native American artworks, from decorated Indian baskets to fetishes, may include feathers from bird species protected under the MBTA. Antique Native American crafts and jewelry may include marine mammal ivory or tortoise shell inlay or beads. Dealers and collectors must carefully consider the age of the object and its materials to be sure that it does not fall under the wide range of protections under US laws.

Information on this website is not legal advice or a substitute for legal advice. The transmission or receipt of the information contained on this website does not create an attorney-client relationship, and you should not act upon such information without seeking professional counsel. This website contains links to other websites. Fitz Gibbon Law, LLC does not necessarily endorse, sponsor, or otherwise approve of the materials at such sites.